As told by Elaine A. Cheesman, Ph.D. – University of Colorado at Colorado Springs – Freedom’s Song

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African Americans to serve in the U.S. Army Air Corp, the forerunner of today’s Air Force, Composed of pilots, navigators, bombardiers, air traffic controllers, maintenance men, and support staff, they were part of the “Tuskegee Experiment” to train African Americans to fly and maintain combat aircraft in World War II. Located at the renowned Tuskegee Institute in central Alabama, the Tuskegee Army Air Field graduated 993 African American pilots between 1942 and 1946.

To fully understand the historical significance of the Tuskegee Airmen, one must first understand the social climate of the time. At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Jim Crow laws, or legal discrimination, had formally existed in the southern states for nearly 60 years. Graphic indications of the Jim Crow laws included voting restrictions, separate schools, “colored” drinking fountains, segregated movie theaters and restaurants and seating in the back of the bus.

In the early days of aviation, Jim Crow laws prevented African Americans from learning to fly in the United States. France opened its doors to aspiring African American pilots. Many African American pilots, like Eugene Bullard, served in the French Lafayette Flying Corps. In 1921, Bessie Coleman, daughter of a slave, trained in France and became the first African American woman pilot.

In 1925 at the height of the Jim Crow era, the military published a report issued by the War College, “The Use of Negro Manpower in War.” This report contained numerous derogatory remarks against the character of African Americans. Although the report offered no supportive evidence, it was accepted as truth and used to block African Americans from serving in the military. Many United States military leaders believed that African Americans lacked sufficient bravery, intelligence, and discipline to fight in combat. Despite that, in World War I (1914-1918), many African American pilots had distinguished records as pilots in the French Air Force.

In 1939, Europe was on the brink of World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt organized the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) to prepare college students for eventual service in the U.S. Army Air Corps. This program was based in existing colleges, segregated by race reflecting the Jim Crow laws. Nearly a decade later, a CPTP was established at the famous Tuskegee Institute in central Alabama. Charles “Chief” Anderson was the chief flight instructor.

To get financial backing for this program, the president of Tuskegee Institute invited members of the Rosenwald fund of Chicago to hold its annual board meeting at the campus. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a member of the board, toured the facilities and observed the pilots. Mrs. Roosevelt persuaded “Chief” Anderson to take her for a plane ride, over the strong objections of the Secret Service. After her visit, Mrs. Roosevelt became a strong supporter, and the Rosenwald Fund loaned the college enough money to construct the Tuskegee Army Air Field.

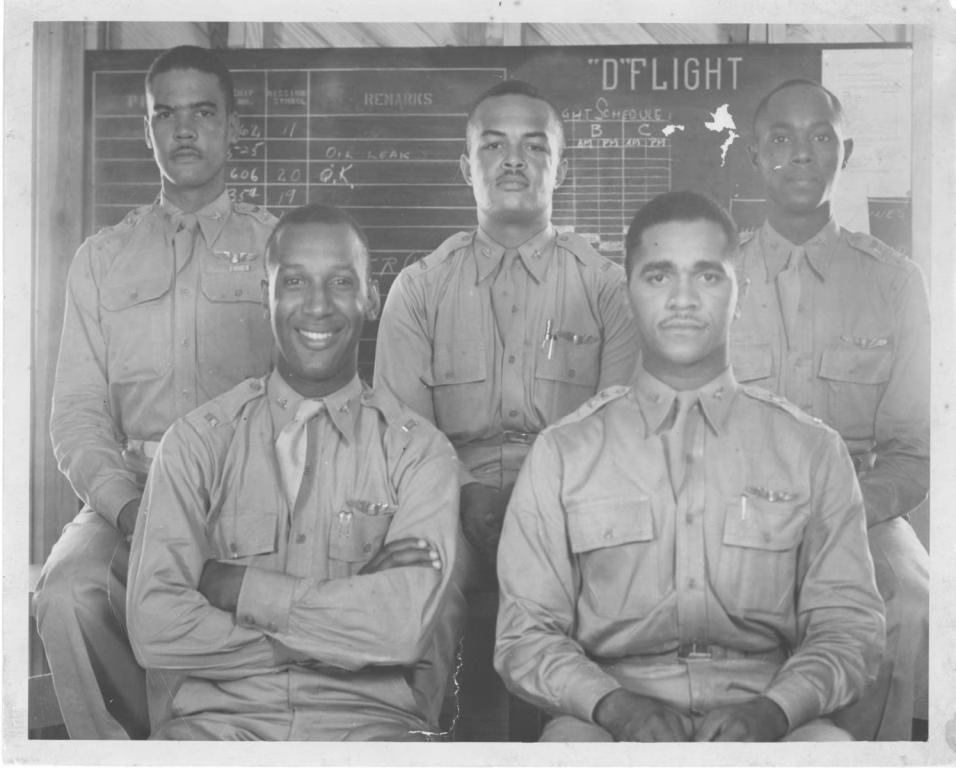

In 1940, the United States faced a crisis, World War II, and looked toward African Americans to fill out the military ranks. The Army Air Corps submitted a plan for an “experiment” to train pilots for all African American fighter squadrons at existing CPTP institutions. Many of the top military brass, firm believers of the War Department’s infamous 1925 report, expected this “experiment” to fail. Tuskegee Institute was selected to be the first Army Air Corps training field, training ground for the African American 99th Fighter Squadron. Of the 13 men in the first pilot training class, only five completed the rigorous five week program to earn their wings. The cadets were painfully aware that this was an experiment. Individual success meant success for all African Americans. If they crashed, all African Americans went down with them.

One of the first graduates of the Tuskegee “experiment” was a West Point graduate, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. Davis was selected as the Commander of the 99th Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group and later became the U.S. Air Force’s first African American General Officer. The success of the Tuskegee Airmen is in large part due to his leadership.

The 99th Fighter Squadron was known as the “lonely eagles” because they were not part of a Fighter Group, customarily composed of three Fighter Squadrons. They first saw combat in Morocco, North Africa. In 1943, the 99th became the fourth and only African American squadron of the all-white 79th Fighter Group. In this group, the Tuskegee Airmen were welcome, and treated as professional equals. This integrated fighter group worked as a team and participated in many victories in Europe.

In 1944, the 99th Squadron was reassigned to the 332nd Fighter Group, an All-African-American group, originally formed in 1943 from three Fighter Squadrons — the 100th, the 301st, and the 302nd. The men of the 99th were not entirely in favor of the transfer; some saw it as a return to segregation. Regardless, together the men of the 332nd achieved many victories. They were known as the Red Tails, because of the distinctive tail markings on their airplanes.

Throughout the war, various attempts were made to discredit African American combat pilots. However, their courage and skill eventually earned them respect from those who first questioned their ability and doubted their courage. The Red Tails became known as experts in bomber escort, and enjoyed the distinction of never losing a bomber they were escorting. No other group in the United States Armed Forces could make that claim.

Despite the impressive battle records in the service of their country, African Americans continued to endure racism at home. African Americans in the military were said to be fighting two wars, one against the enemy in Europe and another against racism. African American soldiers were treated more fairly by European soldiers, even as prisoners of war, then they were in the United States. Back home, military bases were strictly segregated according to Jim Crow practices. When African American officers in the all African American 477th Bombardment group attempted to enter a “white” officer’s club at Freedom Field, they were arrested. It was not until 1948 that President Harry S. Truman issued an executive order to desegregate the military, due in no small part to the bravery and accomplishments of the Tuskegee Airmen.