By Michael Workman

WVSU Associate Professor

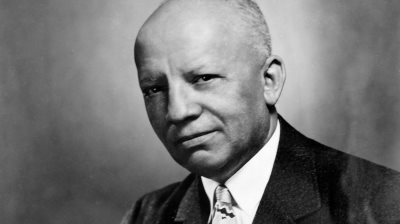

We West Virginians can boast of having more than our share of great African-American leaders who have made significant impacts on American history, including Booker T. Washington and Henry L. Gates. Others nearly as prominent could be listed, but of all the African Americans of distinction from our state, perhaps the one who will end up having the greatest impact on American culture and history is Carter G. Woodson, the educator, historian, and publisher who founded the whole genre of African-American history. Woodson was the one and only black American of slave parentage to earn a Ph.D. in history. He not only wrote and published nineteen books and numerous articles, founded the first scholarly journal dedicated to African-American history, but he also started Negro History Week, which eventually became our current Black History Month.

Although Dr. Woodson’s greatest achievements came later in life while he lived in Washington, D.C., his spent his formative years in West Virginia as a coal miner and educator. Woodson was born in 1875 (see below) near New Canton in Buckingham County, Virginia, just ten years after the close of the Civil War. Both his father and mother were former slaves. Poor, but fiercely independent, his father valued education and taught him to be “polite to everybody, but to insist always on recognition” and respect from all, white or black. Frustrated by the lack of opportunity in Virginia, the young Woodson left the family farm in the Old Dominion in 1892 and joined his older brothers, who had previously migrated to West Virginia. He followed the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway through the New River and Kanawha valleys, first finding work on the railroad laying ties near Charleston, and then joining his brothers to work in the coal mines in nearby Fayette County. Meanwhile, his family, including his including his uncles, moved from Virginia to Huntington, West Virginia, further along the C&O, to work and take advantage of the town’s school for African Americans.

The Woodsons were part of a larger black migration from Virginia and the South into West Virginia that began during Reconstruction and continued until the state’s economy began to slump in the 1920s. The new state offered industrial jobs and a degree of economic and political equality unequaled in any other southern state. The Mountain State was the only southern state in which the black population increased during this period with an upsurge from 17,000 in 1870 to 64,100 in 1910.

Carter G. Woodson went to work at the Nuttallburg mine in the New River coal field at the tender age of seventeen or eighteen in 1892 or shortly thereafter. We know little about his work experience; he wrote next-to-nothing about it. He did write that he once had a close call when a piece of slate nearly fell on him. Woodson did recall, however, some of his activities outside the mine at the mining town, which held 342 residents in 110 company houses in 1890. Here, he received a political education and learned what little was then available on black history. One of his co-workers was a Civil War veteran, Oliver Jones, who operated a tearoom for black miners out of his home where he sold fruit and ice cream and provided a gathering place for black miners. Learning that Woodson was literate, he engaged him to read the daily newspapers to the miners in return for free treats. Woodson later called Jones’s establishment a “godsend,” because it provided products cheaper than the coal company store and served as forum for far-ranging discussions. He described Jones’s home as “all but a reading room,” with volumes that described black history, particularly stories of black Civil War veterans. He would later write that he developed a deep and intense interest in “penetrating the past of [his] people” here. His political education was wide-ranging as he read “speeches, lectures, and essays dealing with civil service reform, reduction of taxes, tariff for revenue only, and free trade.”

Woodson would leave Nuttallburg in 1895, but he did stay long enough to witness at least a small part of one of the grandest public spectacles of the Populist movement: the march of Coxey’s Army to Washington, D.C. in 1894 to gain relief for the unemployed through a national public works program. While the main column of Jacob Coxey’s “industrial army” passed through Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia, one band filtered through the New River corridor on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, stopping to spend a night in the idled coke ovens at Nuttallburg. Woodson must have been impressed by the idealism and dedication of the marchers for he became knowledgeable about the Populist doctrines of Tom Watson and William Jennings Bryan.

Never one to let grass grow under his feet, Woodson left Nuttallburg in 1895 to return to Huntington, where his family lived, to attend Frederick Douglass High School, the city’s only black high school. He graduated in two years, and then in 1897 enrolled at Berea College in Kentucky, one of the few colleges of the time which offered interracial education. He matriculated for only one quarter at Berea, but he picked up enough credits later at the University of Chicago to get his bachelor’s degree from Berea in 1903. He took a classical curriculum, with a smattering of the emerging social sciences. For the first time, he studied history on a formal basis. He also participated in the vocational training required at Berea. Later, he would argue in several of his writings that this type of education, a combination of classical courses and vocational training, was best for blacks.

Woodson also returned to Fayette County during this period to teach at a school in Winona, just five miles from Nuttallburg. According to his biographer, he taught at “a school established by black miners for their children” from 1897 to 1900. He would later write (in 1922) that black West Virginians became excited in education during his teaching days in Winona, and that “often Negro children in groups of four or five were thus trained in the backward districts where they received sufficient inspiration to come to larger schools for more systematic training.” Woodson was one of those teachers who helped inspire this thirst for learning.

Winona, named for the wife of prominent hotel owner William Gwinn, was a coal mining town situated along the Keeney’s Creek Branch of the C&O Railway. Built by John Nuttall to open-up the 30,000 acres of coal lands of which he owned the mineral rights, the branch ran from Nuttallburg up the New River Gorge to the highlands above and terminated in about 10 miles at Lookout. Nuttall completed the first five miles to Winona by 1893 and then later sold it to the C&O; he leased his coal lands to associates and employees of his earlier operations. By the time Woodson arrived in Winona in 1898 there were at least two major coal operations near the town, the Ballinger Coal Company and the Smokeless mine owned by the Masters Coal Company. Both operated company stores and built a number of company houses at Winona. Other mines and coal communities were located up and down the Keeney’s Creek Branch line.

Winona was a bustling, wide-open, and independent community in 1900 with a population of 850, according to the Federal Census. The mining town boosted several independent businesses, partly because the coal companies did not control the surface rights of the land. John Cavalier, historian of Fayette County, noted that during its prosperous period (which extended past the 1890s until the 1950s), Winona had a drug store, several general merchandise stores, dry goods stores, a meat market, a pool room, a millinery business, a barber shop, several hotels, a lodging house, a bank, and a movie theatre. Several fraternal organization were represented at Winona, including a Masonic lodge chartered in 1903. Several churches stood at Winona, as well, along with a one-room school, presumably a white school that started in 1895.

The African-American population of Winona stood at 259 in 1900—29% of the total population. Winona’s African Americans originated overwhelmingly in Virginia, though some were born in West Virginia (with parents from the Old Dominion). Only a very few individuals were born in states other than Virginia or West Virginia—nine from North Carolina, three from Ohio, and one each from Kentucky, Alabama, and Pennsylvania. The occupation of all but ten of the males was coal mining, either as miner or mine laborer. The eleven non-coal occupations were held by six railroad workers, three construction workers, one barber, and one public school teacher (Carter G. Woodson). All of the black females for which an occupation was listed were servants or housekeepers. None of the households were inter-racial, but it seems plain from the order in which the enumerator listed persons that black families were interspersed among white families. This suggests that there was no rigid segregation in the town. For the most part, though, both blacks and whites were listed in blocks of several households, suggesting that there were black and white sections or neighborhoods in the community. One other notable piece of information gathered by the enumerator suggests that there was little or no idleness in the town: Not one adult in the town was listed as unemployed during the year preceding the enumerator’s survey!

The Federal Census provides some interesting, and perhaps controversial, information about Carter G. Woodson. He is listed as a “boarder” in the household of William M. Shorts. Also in the household were William’s wife, Sallie (whose father was born in Africa—the only person from Winona with that distinction) and two daughters, a female servant and two miners (one from Alabama). Although the date for his birth is commonly given by his biographers and other sources as 1875, the enumerator lists it as February, 1877. He is depicted as 23 years old, single, born in Virginia, as were his parents, and, as an occupation, a “Public School Teacher.” This suggests that “school established by black miners for their children” probably transitioned into a public school following the 1899 amendment to the state school bill, which required each county to establish primary schools for black children between the ages of six and twenty-one.

Woodson left Winona in 1900 in pursuit of greater opportunity in Huntington. He taught history and was the principal at Douglass High School until 1903, when opportunity knocked again. After the Spanish-American war and the defeat of the Filipino insurrection in 1902, the U.S. launched a far-ranging social and economic aid program under the leadership of William Howard Taft. Woodson signed up and spent from 1903 to 1907 teaching in the Philippines and serving as supervisor of schools and teacher-training in Pangasinan province. After a six-month world tour, Woodson returned to the United States to attend graduate school. He obtained his master’s degree in history at the University of Chicago in 1908, where he wrote his thesis on 18th century French diplomatic policy. His quest for a doctorate in history from Harvard took longer, however, partly because he had to hold down a full-time job teaching throughout most of his studies. Enrolling at Harvard in 1907, his dissertation was not accepted until 1912. With Frederick Jackson Turner’s celebrated “frontier thesis” in vogue, his professors had little interest in black history. Woodson would later write that he was upset at their attitude of skepticism that African Americans had made any contribution to American history beyond their enslavement. To gain his degree, Woodson worked within Turner’s paradigm and wrote on the separation of West Virginia from Virginia, focusing on the economic causes of the sectional struggle between East and West. The dissertation was never published, as Charles Henry Ambler’s Sectionalism in Virginia from 1776 to 1861, which appeared in 1910, superseded Woodson’s work. Woodson would later write that his education at Harvard was a good example of the “mis-education of the Negro,” where he encountered “traducers of the race,” but he did learn bibliographic and research skills and further develop his views on American history. And, he was the second African American to receive the doctorate at Harvard, right behind W.E.B. DuBois, as well as the only American born of slave parents to earn that degree.

Woodson had re-located from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1911. Here he would teach in the segregated black schools of the nation’s capitol, publish his first works on the history of black education, and found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. The latter became the seedbed for several programs in African-American history and education that Woodson developed later. Perhaps the most important of these efforts was the establishment of the Journal of Negro History which published its first number in January, 1916. Both the association and the journal remain active today. The journal has undergone two name changes, and continues as the pre-eminent organ for African-American history under the title, The Journal of African American History.

After nearly a decade teaching in the black public schools of Washington, D.C., Woodson obtained an appointment at Howard University in 1919 to head-up the History Department. His stay there was short-lived (even for Woodson) due to disagreements with the institution’s president. In 1920 he was dismissed from Howard. Fortunate to be on close terms with John W. Davis, president of West Virginia Collegiate Institute (later West Virginia State University), Woodson received an appointment as dean of the college later in that same year.

Under the dynamic leadership of Woodson and President Davis, WVCI grew dramatically and expanded its curriculum. Enrollment grew from 297 to 445 in Woodson’s first year. New courses were offered in a host of new subjects. Woodson was particularly sympathetic to the many middle-aged students from mining towns who matriculated because of their thirst for knowledge and because he, too, had been a latecomer to higher education. During his two-year tenure at the institute, Woodson taught, administered the college as dean, and undertook a research project on the history of black education in West Virginia. The result, “Early History of Negro Education in West Virginia,” was published in the Journal which he continued to edit.

With his resignation from the West Virginia Collegiate Institute in June, 1922, Woodson moved to Washington, D.C. and purchased a three-story row house at 1538 9th Street. He would use the two lower floors for research and activities of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, while he lived on the 3rd floor. Thus, Woodson, entered a new phase in his life. He would never hold an academic appointment or teach in public schools again. He would never again play a direct role in the life and development of West Virginia. Instead, he would devote the remainder of his life raising money and building-up the Association, editing his beloved Journal writing for another publication he founded in 1937, the Negro History Bulletin, and giving public lectures. He would devote the rest of his career to ensuring that the truth about African-American history be told.

As director of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Woodson launched the annual celebration of Negro History Week in 1926. He chose the second week of February for the annual event to commemorate the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Woodson sent out a veritable flood of literature promoting the event, emphasizing the importance of recognizing black achievements and contributions, and suggesting various ways to celebrate the week. As Woodson later wrote, the education departments of three states, North Carolina, Delaware, and West Virginia, celebrated the event in its first year, and he was frankly surprised by the favorable reception to his idea. Notable African-American contemporaries, including W.E. B. DuBois and Rayford Logan were impressed. DuBois considered it one of the greatest accomplishment to come out of the 1920s. The weeklong celebration was expanded into Black History Month in 1976 by President Gerald Ford who used a Bicentennial address to urge Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black American s in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

NOTES

1. “New River Gorge” site created by National Park Service

http://www.nps.gov/neri/learn/historyculture/carter-g-woodson.htm

2. “Bridge Day” site created by New River Gorge Bridge Day Commission

http://officialbridgeday.com/carter-g-woodson/

3. “Biography of Carter G. Woodson” site created by About.com

http://afroamhistory.about.com/od/biographies/a/A-Biography-Of-Carter-G-Woodson.htm

4. “The Education of the Negro” book

Bibliography

“Biography of Black Historian Carter G. Woodson.” About.com Education. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://afroamhistory.about.com/od/biographies/a/A-Biography-Of-Carter-G-Woodson.htm

“Carter G. Woodson Made History in the New River Gorge.” Bridge Day. January 10, 2015. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://officialbridgeday.com/carter-g-woodson/

United States. National Park Service. “Carter G. Woodson.” National Park Service. December 1, 2015. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://www.nps.gov/neri/learn/historyculture/carter-g-woodson.htm

Woodson, Carter Godwin. The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. New York: Arno Press, 1968